By Grizz

The American Chestnut was once the most important and valuable tree in eastern North America. Now, it is nearly extinct. This is the story of how an invasive species killed off this special tree and, in the process, helped exterminate self-sufficient agrarian life in Appalachia.

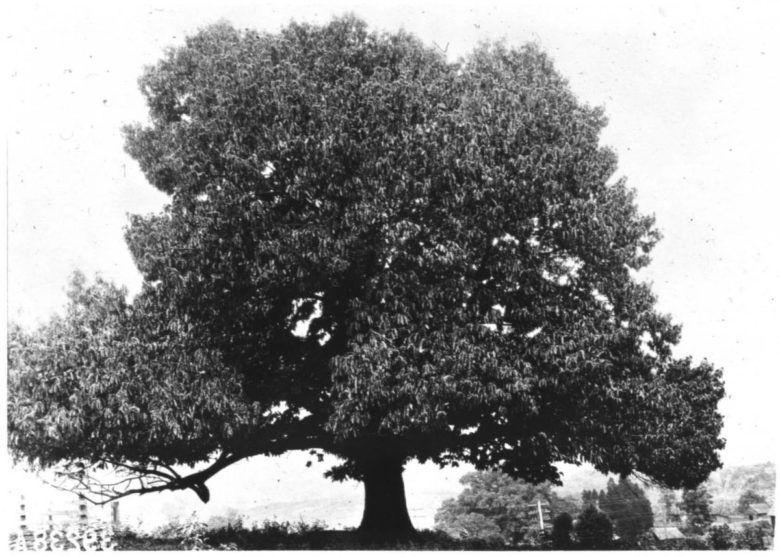

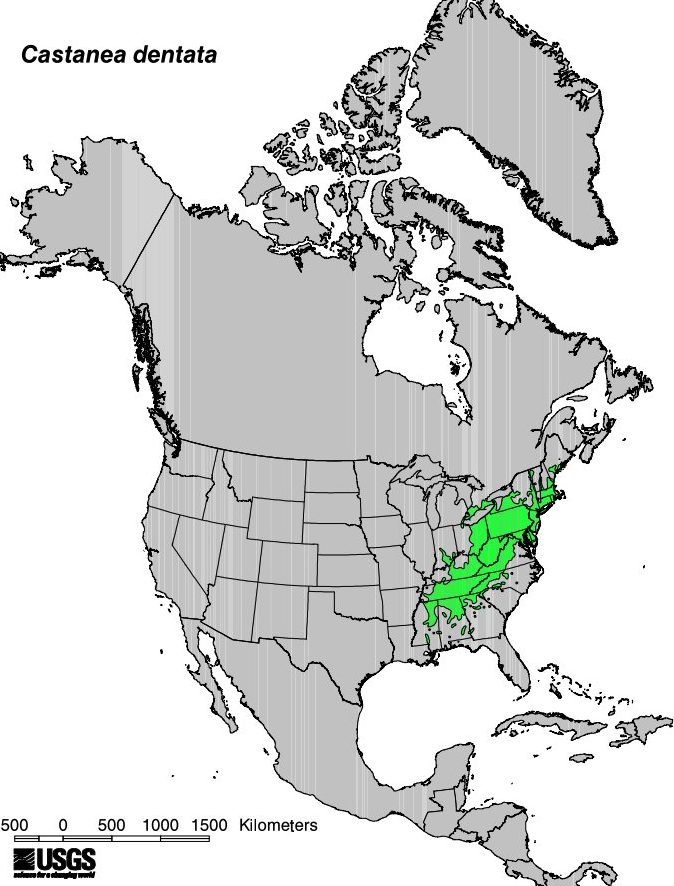

The American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a hardwood tree native to eastern North America. It is considered the finest chestnut tree in the world. Growing up to 17 feet wide and up to 120 feet tall, old chestnuts were among the most stunning specimens in the eastern forests.

When European settlers arrived in the New World, the American Chestnut was likely the most common tree they encountered. In some areas of Appalachia, nearly 1 in 2 trees in any given forest was an American Chestnut.

The earliest use of the chestnut was probably as a fencing wood – few woods split easier and straighter while being as light and durable. Early colonial settlers built “Virginia rail fences” out of chestnut, which required no posts and lasted a life time.

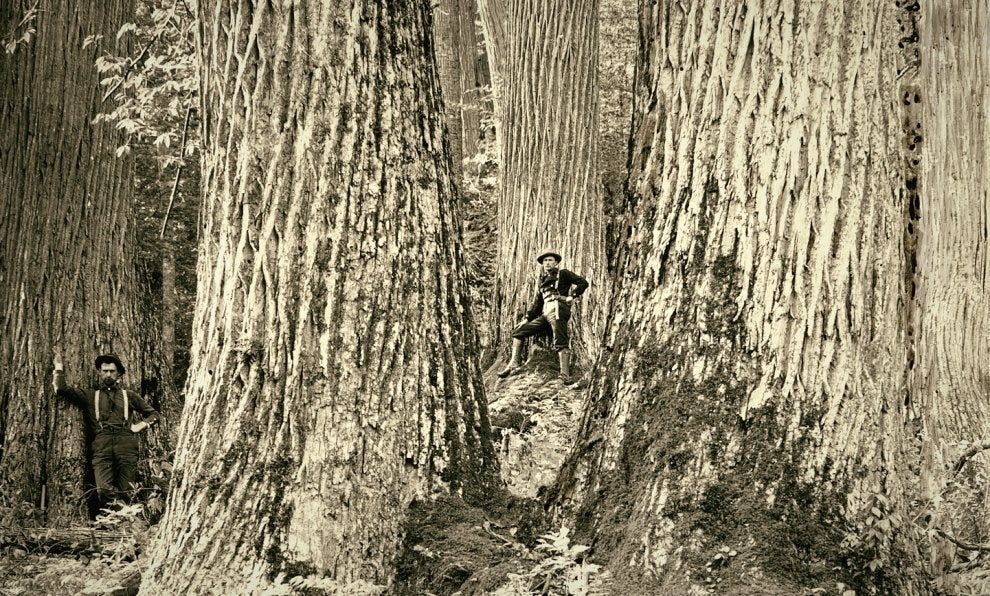

It was unsurpassed as a building material because it grew straight and was highly rot-resistant, insect-proof, and weather-resistant. Some grew so large that an entire cabin was constructed from a single tree in Tennessee.

Its uses go far beyond just building, though. Chestnuts are highly nutritious and were a staple in the diet of animals in the region, providing most of the fall food for wildlife such as the white-tailed deer, wild turkey, and the now extinct passenger pigeon.

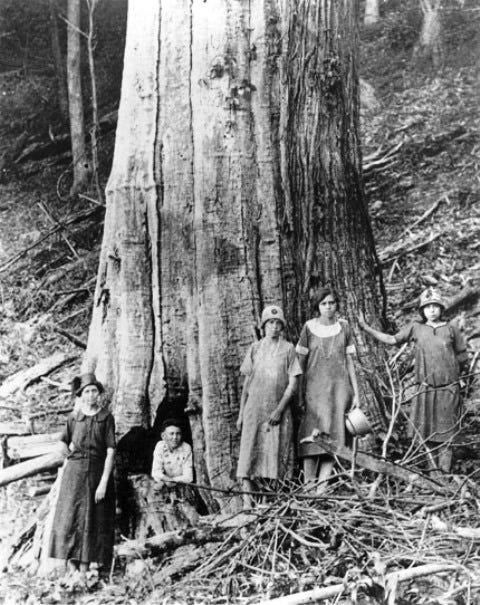

Humans also frequently consumed chestnuts. With the first frost in October, children were often sent to the woods to collect sacks of chestnuts, which were either roasted or brought by wagon to country stores to be sold or exchanged for other commodities.

“Chestnuts roasting on an open fire” would produce a delightful aroma that spread through the hills. In the 1800s to early 1900s, you could hardly walk through Appalachian hollows in the fall and winter without smelling chestnuts baking in people’s homes.

Similarly, many parts of the American Chestnut tree were used as medicine. The Cherokee used leaves to alleviate heart troubles, and the sprouts were sometimes made into a tea to treat sores and wounds. The nuts were also used to treat ailments such as whooping cough.

Hogs were easy to raise in the mountains as they were sent to roam free in the woods to feast on the abundance of chestnuts littering the forest floor. “Mountain pork”, which had a special flavor from their chestnut diet, became a highly sought after commodity.

The American Chestnut allowed farmers to raise livestock at virtually no cost for many months out of the year by applying one of the earliest forms of silvopasture in America. By having chestnut trees, rural people had money and meat on the table for centuries.

Hollows in old-growth chestnut trees were massive. One account from an early ranger in the Smoky Mountains said of a large chestnut, “A man lost some stock during a snowstorm and later found them safe in a hollow chestnut tree.”

Life among these trees was looking up.

Around the turn of the 20th century, an invasive pest known as the “Chestnut Blight” was introduced to American Chestnut trees in New York City through shipments of Chinese chestnuts from East Asia. It spread rapidly, as the American Chestnut had no resistance to the pest.

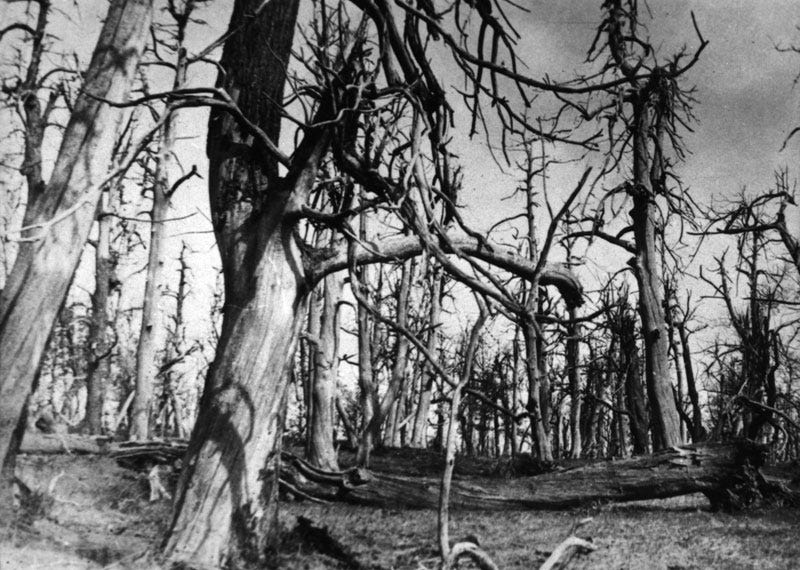

Spreading at an astounding rate of 50 miles/year, it only took 30 years to eradicate most of the American Chestnuts in the eastern U.S., meaning that approximately 4 billion chestnut trees were killed by the late 1930s. The photo below (date unknown) shows a chestnut grove devastated by blight.

Farmers and woodlot owners were encouraged to harvest their remaining chestnut trees quickly, as their value decreased rapidly upon deterioration. This may have sped up the extinction process, as trees with a small amount of blight resistance may have been killed off.

When chestnuts began dying off in large droves, many locals thought the entire ecosystem was dying. In a way, they were right. Turkeys began disappearing, and squirrel numbers decreased to a tenth of what they were before. Black bears never seemed to get as fat as they used to.

Many organisms relied entirely on the American Chestnut tree to survive. At least seven native moths became extinct in southern Appalachia, including the American Chestnut Moth.

Life without chestnuts was almost unthinkable; the tree had been so deeply connected to life in Appalachia for centuries. No longer able to raise hogs and cattle in the woods or gather chestnuts for sale, rural people increasingly looked to the urban center for salvation.

It became much more difficult to maintain a self-sufficient, agrarian life in the mountains. As industrialization rapidly expanded, the death of the chestnut seemed to extinguish mountain folks’ last hope at maintaining life as they had known it for four centuries.

In the years since, biologists and foresters have been attempting to cross-breed and modify the chestnut to improve its resistance to the blight. Many of these projects were abandoned by the 1960s, but some still remain today.

Unfortunately, the damage has already been done. Today, most Appalachians do not remember life among these trees. Despite it being such an important part of our history, we will never again experience the true glory of the American Chestnut. R.I.P.

You can read Grizz’s essays at his new website Ecological Samizdat, as well as his thought-provoking musings on Twitter.